The V&A’s latest exhibition is a glittering exploration of Cartier. More than 350 pieces trace the house’s evolution through craft, culture and style, as the Field Grey team discovered on a recent Field Trip ‘up west‘.

Beyond the sparkle, what stood out was Cartier’s sensitivity to changing fashions and global influence. The exhibition opens with early Russian-inspired works and closes with bold modernism, showing how the brand moved with – and often ahead of – the times.

Founded by Louis-François Cartier in 1847, Cartier emerged at a moment of transformation in Paris. The city was the epicentre of cultural reinvention, a place where luxury and modernity met. This was a time when fashion began to reflect personal identity and aspiration. As the bourgeoisie rose, so did the appetite for ornamentation: fine jewellery, tailored waistcoats and accessories that spoke of status and taste.

The brothers who built a brand

Louis-François’s modest workshop grew into an empire through the vision and charisma of his grandsons, Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier. Each brought something unique to the brand, not just in business acumen but in personal style. Their presence became a form of branding in itself, aligning the house of Cartier with refinement, intelligence and modern elegance.

A family of distinction

A striking 1920s family portrait captures this perfectly. Alfred Cartier, their father, stands with a fob chain draped across his buttoned waistcoat, a classic beret perched on his head – a picture of dignified French tradition.

His sons, meanwhile, radiate international flair. Louis, often seen as the creative force behind the brand, was suave and ultra-confident, reflecting the tastes of Paris’s avant-garde. Pierre, who expanded Cartier to New York, exuded transatlantic polish. Jacques, responsible for London, was especially dapper – dark hair slicked back, cigarette held with relaxed sophistication, shoes gleaming.

Jewellery as storytelling

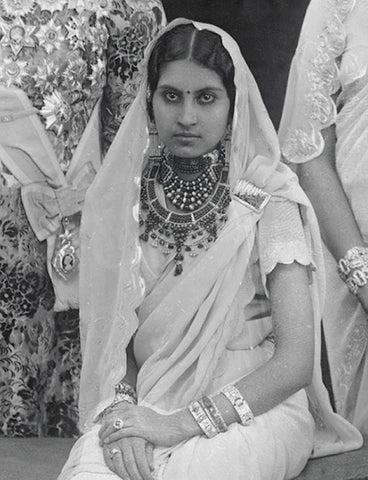

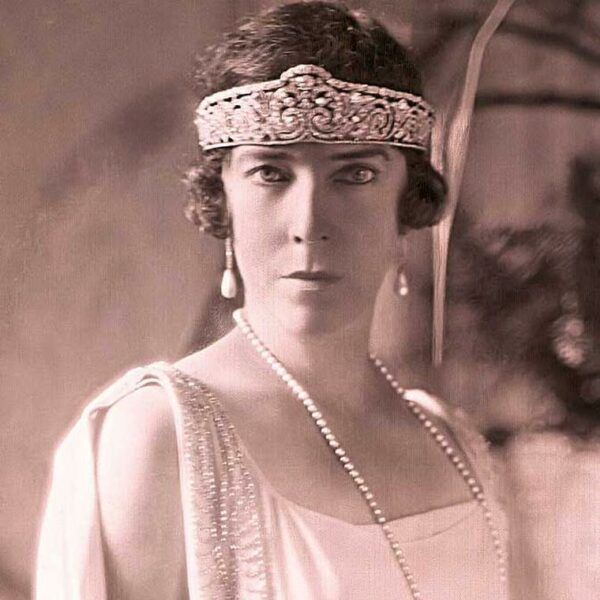

Their refined presentation wasn’t for show. It reflected their understanding of jewellery as storytelling. Cartier’s creations became part of the visual language of royalty and aristocracy. In the Belle Époque, they dressed European princesses and Russian Grand Duchesses with diamond tiaras, platinum garlands and impossibly delicate settings. In the early 20th century, Cartier became famed for its commissions from Indian Maharajahs – vivid, sculptural pieces that blended Mughal opulence with Parisian craft.

Ahead of the curve

Fashion was always part of Cartier’s success. Jacques Cartier once wrote to his brothers about the changing styles post World War I as women became flappers – how bobbed hairstyles created demand for longer earrings and a new style of bandeau headband worn low on the forehead. These shifts in silhouette were opportunities. The Cartiers anticipated cultural change and responded with pieces that felt both timely and timeless.

Today, Cartier still stands for luxury and aspiration, but in a very different world. The V&A exhibition focuses on beauty and heritage, but it leaves out what the brand means now. Like many legacy names, Cartier’s had to reckon with modern expectations around sustainability, ethics and purpose. It’s made moves, from biodiversity initiatives to co-founding the Watch & Jewellery Initiative 2030. But at heart, it remains a symbol of elite craftsmanship and timeless style. Perhaps that’s the point: Cartier doesn’t need to reinvent itself to stay relevant. It just needs to keep reminding us why it became iconic in the first place.

Images courtesy of thejewelleryeditor.com, sothebys.com, vibewithmoi.com